Single and Combined administrations of Artemether-lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac indicated Oxidative Imbalance in Female Wistar Rats

- 1. Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, USA

Abstract

Despite governmental regulations on the use of anti-malarial, antibiotic, and analgesic medications, reports indicate a rise in their misuse. This study evaluated the effects of artemether-lumefantrine (AL), ciprofloxacin (CPX), and diclofenac (DFC) on oxidative stress markers in female Wistar rats. 96 female Wistar rats were divided into 8 groups of 12. Group 1 served as control, while groups 2-8 were administered AL, CPX, DFC, AL+CPX, AL+DFC, CPX+DFC, and AL+CPX+DFC, respectively. Doses were 178 mg/kg for AL, 185 mg/kg for CPX, and 9 mg/kg for DFC. After oral administration for 6 and 12 weeks, blood and tissues (liver, kidney, heart, spleen, and small intestine) were collected for biochemical and histological analysis. Oxidative stress markers {nitric oxide, thiols, catalase, superoxide dismutase, paraoxonase, protein carbonyl, malondialdehyde, and oxidized low density lipoprotein cholesterol (oxLDL-C)}, were assessed in the serum and tissues. Data was analysed using GraphPad Prism 5, with one-way ANOVA at a 5% significance level. Results showed significant increases (p?0.05) in protein carbonyl, oxLDL-C, nitric oxide, catalase, superoxide dismutase, and paraoxonase across the treatment groups at week 6 and 12. Group 8 exhibited marked reduction (p?0.05) in glutathione levels and catalase activity at week 6 and 12, respectively. Histological analyses revealed tissue alterations in the liver, kidney, heart, spleen, and small intestine in all treatment groups at week 6 and 12. Co-administration of AL, CPX, and DFC disrupted the oxidative balance, leading to dysfunctions in the liver, kidney, spleen, heart, and small intestine. Consequently, the indiscriminate use of these drug combinations should be avoided.

Keywords

• Artemether-lumefantrine

• Ciprofloxacin

• Diclofenac

• Oxidative stress

Citation

Oluwafunmilayo J (2025) Single and Combined administrations of Artemether-lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac indicated Oxidative Imbalance in Female Wistar Rats. J Pharmacol Clin Toxicol 13(2):1192.

INTRODUCTION

The practice of self-medication is a global problem with high prevalence in developing countries [1,2]. Self medication involves the intermittent or continued use of a drug for a chronic or recurrent condition by the patient, after an initial diagnosis and prescription by a physician [2,3]. Unfortunately, many lives have been endangered by the practice of self-medication and it has been associated with low life expectancy rates due to high incidence of adverse drug reactions [1,4,5], hence, it remains a significant health concern [1,6].In developing countries, the high incidence of malaria [7], and microbial infections [8], is a major contributor to the practice of self-medication with several drugs such as anti-malaria, analgesic and antibacterial in frequent use [6]. In 2010, the World Health Organization reported that the recurrence of malaria in malaria endemic areas, such as Nigeria resulted in the uncontrolled use of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), with artemether-lumefantrine being the most commonly used [9]. Artemisinins target malaria-infected erythrocytes and destroy the parasites through production of free radicals which are higly reactive and could cause significant damage to the biological system [10- 12].Previous studies also revealed that the high incidence of malaria and enteric fever co-infection [13], has led to the frequent co-administration of antimalarial drugs and antibiotics by health care providers [14]. Hence, the co-administration of artemether-lumefantrine and ciprofloxacin is a common practice in Nigeria in the treatment of malaria and enteric fever co-infection [15]. Ciprofloxacin is a synthetic flouroquinolone used for the treatment of various bacterial infections such as respiratory tract and urinary tract infections [16]. It induces the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that enhances its antibacterial activities [17-20].Analgesics such as paracetamol and diclofenac are prescribed as antipyretic agents to reduce fever and pains associated with common malaria [21], while ciprofloxacin is also frequently prescribed with analgesics for the management of infection, pain and inflammation in the treatment of several infections [22,23]. Diclofenac (DFC) is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID), analgesic and antipyretic drug that is used globally to relieve pain and fever [24,25]. In addition, diclofenac is easily accessible as an over-the-counter medication, promoting its misuse and potential for abuse [26,27].The co-administration of two or more drugs is often necessary for effective treatment of co-existing diseases; however, it is usually followed by several implications such as opposition, alteration, synergism, and potentiating [28]. For instance, the co-administration of nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs such as diclofenac with antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin may magnify the toxic effects of both drugs [29-31]. Previous studies have reported the toxicological effects of the separate administration of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac [32-35], however, there is currently no documentation on the effects of the combination of these drugs on oxidative status. Therefore, this study evaluated the effect of the co administration of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac on oxidative stress indices in female Wistar rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drugs, Reagents, Kits and Chemicals

The drugs (artemether-Lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac), were obtained from a reputable pharmacy in South-West Nigeria. The quantitative assay kits for reduced glutathione, total thiol, protein thiol, malodialdehye, superoxide dismutase and catalase were products of Fortress Diagnostic Laboratory, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom. Assay kits for protein carbonyl, oxidized low-density lipoprotein and paraoxonase, were products of Elabscience Biotechnology Inc., Texas, USA. All other chemicals were products of Sigma Aldrich, Wisconsin USA.

Experimental Animals

A total of 96 female Wistar rats, each weighing between 90-110 g, were acquired from the Animal House at Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Oyo State, Nigeria. All animal handling and experimental procedures followed the guidelines established by the National Research Council [36].

Experimental Design

The rats were randomly assigned to eight groups, with twelve rats per group, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Grouping of Animals and Treatment.

|

Groups |

Treatment |

|

1 |

Control |

|

2 |

Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) |

|

3 |

Ciprofloxacin (CPX) |

|

4 |

Diclofenac (DFC) |

|

5 |

Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX) |

|

6 |

Artemether-Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL +DFC) |

|

7 |

Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX + DFC) |

|

8 |

Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (AL + CPX +DFC) |

They were given a two-week acclimatization period, during which their weight and behavior were closely monitored for any significant changes. After this period, the drug administration began. Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin, and Diclofenac were administered orally, with dosages determined based on the manufacturer’s recommendations and conversion from human to animal doses as outlined in [37]. The drugs were dissolved in distilled water and administered once daily at 8:00 am using a 1 ml cannula syringe. Artemether-Lumefantrine was given at a dose of 178 mg/kg body weight for three consecutive days every two weeks. Ciprofloxacin was administered at a dose of 185 mg/kg body weight for five days each week. Diclofenac was given at a dose of 9 mg/kg body weight for ten days every two weeks.

Collection of Samples

After a six-week period of drug administration, the rats were fasted overnight and anesthetized with diethyl ether. The chest cavity was swiftly opened, and blood was extracted by puncturing the heart using a new syringe for each rat. Blood samples were collected into plain tubes, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes to obtain serum, which was then carefully transferred to labeled bottles and stored at below 4°C for future biochemical analysis.The liver, kidney, heart, small intestine, and spleen were promptly removed, washed to remove blood, and rinsed with normal saline. Each organ was weighed, and a section of each was preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathological assessment. 0.2 g samples of liver and heart tissues were homogenized separately in a 0.25 M sucrose solution (1:4 ratio), using a laboratory homogenizer, then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatants were collected in Eppendorf tubes and stored at 4°C for further analysis. The same procedure was repeated after twelve weeks of drug administration.

Biochemical Assay Methods

The total thiol and protein thiol levels in serum and liver tissues were measured following the method outlined by [38]. The concentration of reduced glutathione (GSH) was assessed using the technique of [39]. Protein carbonyl and malondialdehyde levels were measured using the methods provided in the assay kits. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined using techniques described by [40] and [41]. Catalase activity was evaluated according to [42]. Analyses of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxidized-LDL) and paraoxonase (PON 1) were performed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) based on the sandwich immunoassay principle.

Histological Analysis

Histological procedures followed the techniques described by [43].

Statistical Analysis

The study utilized a completely randomized design (CRD) and statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 5. Data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Tukey’s Post Hoc test applied to determine variations among treatment groups. Results were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), and statistical significance was set at a p-value of < 0.05, denoted by appropriate letters and symbols.

RESULTS

Effect of Artemether-lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac on Antioxidants.

The data presented in Table 2 indicated no significant difference in serum and liver total thiol concentrations (p > 0.05), among the treatment groups 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 compared to the control (group 1) at both week 6 and week 12. However, at week 12, a significant increase (p < 0.05) in liver total thiol levels was observed in group 7 compared to group 5. At week 12, groups 2 and 7 also showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in liver total thiol levels compared to week 6.

Table 2: Total Thiol Concentrations in Serum and Liver of Rats Treated with Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac.

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Total Thiol (mM) |

Serum |

S |

2.16±0.12a |

2.91±0.23a |

2.48±0.16a |

2.60±0.22a |

2.59±0.15a |

2.48±0.13a |

1.96±0.09a |

1.99±0.10a |

|

T |

2.58±0.42a |

3.13± 0.27a |

3.16±0.42a |

3.52±0.44a |

2.56±0.14a |

2.56±0.18a |

2.36±0.21a |

2.73±0.342a |

||

|

|

Liver |

S |

3.79±0.25a |

3.73±0.13a |

3.82±0.35a |

3.93±0.20a |

3.20±0.17ab |

4.12±0.15a |

3.47±0.25ac* |

3.46±0.25a |

|

T |

4.58±0.49a |

5.02±0.29a |

4.81±0.39a |

5.06±0.14a |

3.56±0.45a |

5.02±0.41a |

5.26±0.10a |

4.18±0.45a |

Note: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6- Artemether Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin+ Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC).

S= 6 weeks and T= 12weeks.

Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p < 0.05). Serum (Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1); Liver (Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1; Week 12: aNo significant difference with group 1, ab Significant difference with group 7, ac Significant difference with group 5. * Significant difference between Week 6 and Week 12.

The results in Table 3 depicts the serum and liver concentrations of protein thiol in rats administered artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac. No significant differences (p > 0.05) in liver protein thiol levels were noted among groups 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 compared to the control (group 1) at both week 6 and week 12. A significant decrease (p < 0.05) was recorded in liver protein thiol levels in group 8 compared to group 3 at week 6. Furthermore, at week 12, group 5 exhibited significantly lower (p < 0.05) liver protein thiol levels compared to the control and groups 6 and 7. Conversely, liver protein thiol levels in groups 6 and 7 increased significantly (p < 0.05) at week 12 compared to week 6. Additionally, at week 12, serum protein thiol levels in group 4 significantly increased (p < 0.05) compared to the control and groups 2 and 6. Significant increases (p < 0.05) in serum protein thiol levels were also observed in groups 3, 4, and 7 at week 12 compared to week 6.

Table 3: Protein Thiol Concentrations in Serum and Liver of Rats Treated with Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac.

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Protein Thiol (mM) |

Serum |

S |

1.06±0.20a |

1.38±0.23a |

1.08±0.25a |

1.25±0.17a |

1.38± 0.08a |

1.37±0.18a |

0.73±0.13a |

1.33±0.07a |

|

|

|

T |

0.99±0.26a |

1.46± 0.09 a |

1.93±0.31a |

2.54±0.38b |

1.48± 0.11ab |

0.94±0.15a |

1.65±0.16ab |

1.62±0.27ab |

|

|

Liver |

S |

2.40±0.34a |

2.75±0.21a |

3.35± 0.32ab |

3.53±0.26a |

1.76±0.19ac |

2.85±0.20a |

2.04±0.26a |

1.76±0.14a |

|

|

|

T |

3.36±0.39a |

3.75±0.26ad |

2.82±0.12 a |

2.79±0.22 a |

2.21±0.42ae |

4.05±0.20 ad |

3.67±0.15ad |

2.59±0.39a |

Note: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6- Artemether Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin+ Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC).

S= 6 weeks and T= 12weeks.

Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p < 0.05). Serum (Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1; Week 12: aNo significant difference with group 1, b Significant difference with groups 1, 2 and 6, ab No significant difference with groups 3, 5 and 8). Liver (Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1, , abSignificant difference with group 5, acSignificant difference with group 3; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1, ad Significant difference with group 5, ae Significant difference with groups 2, 5 and 7). * Significant difference between Week 6 and Week 12.

As presented in Table 4, no significant changes (p > 0.05) was recorded in liver reduced glutathione (GSH) levels across all treatment groups 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 compared to the control (group 1) at week 6 and week 12. However, at week 6, group 8 showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in liver GSH concentration compared to group 2. Additionally, a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in serum GSH concentration was observed in group 8 compared to groups 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7. At week 12, significant decreases (p < 0.05) in serum GSH levels were noted in group 7 compared to the control and groups 2, 3, 4, and 6. Group 5 also showed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in serum GSH levels compared to group 6, while group 8 had lower (p < 0.05) serum GSH levels compared to group 6. Serum GSH levels in groups 6 and 7 decreased significantly (p < 0.05) at week 12 compared to week 6, whereas group 8 exhibited a significant increase (p < 0.05) in serum GSH levels at 12 weeks compared to week 6.

Table 4: Reduced Glutathione Concentrations in Serum and Liver of Rats Treated with Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac.

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Reduced Glutathione (mM) |

Serum |

S |

1.10±0.16a |

1.57±0.04ab |

1.40±0.10ab |

1.19± 0.12ab |

1.21± 0.07ab |

1.11±0.08a* |

1.23±0.11ab* |

0.66±0.05ac* |

|

|

|

T |

1.28±0.12 a |

1.48±0.05a |

1.56 ±0.10af |

1.34±0.06a |

1.08±0.05abe |

1.62±0.12af |

0.75±0.04b |

1.12±0.11abe |

|

|

Liver |

S |

1.39±0.14a |

1.06±0.08ab |

1.18±0.16a |

1.26±0.09a |

1.44±0.07a |

1.27±0.12a |

1.43±0.11a |

1.87±0.18ac |

|

|

|

T |

1.22±0.17a |

1.27±0.07a |

1.27±0.20a |

.53±0.14a |

1.49±0.20a |

1.49±0.15a |

1.59±0.12a |

1.87±0.09a |

Note: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6- Artemether- Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin+ Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC).

S= 6 weeks and T= 12weeks.

Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p < 0.05).

Serum (Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1 , ab Significant difference with group 8, ac Significant difference with groups 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1, b Significant difference with groups 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6, af Significant difference with groups 5 and 8, abe Significant difference with groups 3 and 6) Liver (Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1, ab Significant difference with group 7, ac Significant difference with group 2; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1).

* Significant difference between Week 6 and Week 12.

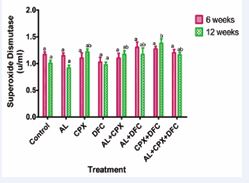

In the results presented in Figure 1, no significant difference was observed in the liver superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity (p ? 0.05) across the treatment groups 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 when compared with the control (group 1) at week 6. At week 12, however, group 8 had a significant increase (p < 0.05) in liver SOD activity compared to the control and groups 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 1 Superoxide Dismutase Activities in Rats Administered with Oral Doses of Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac. Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine+ Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n=5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p<0.05). Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1, b Significant difference with groups 1, 2, 3 and 4, ab No significant difference with group 7.

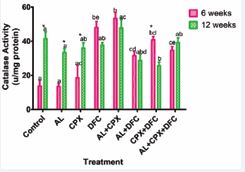

Figure 2 depicts liver catalase activities in rats treated with artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac. Significant increases (p < 0.05) in liver catalase activity were observed in groups 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 at week 6 compared to the control and groups 2 and 3. Groups 4, 5, and 7 also had significantly higher (p < 0.05) liver catalase activity compared to group 3. Conversely, group F showed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in liver catalase activity compared to group 4, and groups 6 and 8 had reduced (p < 0.05) catalase activity compared to group 5. At week 12, liver catalase activity in group 7 significantly decreased (p < 0.05) compared to the control and groups 2 and 5, while group 4 also showed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) compared to group 5. Groups 6 and 7 had significantly lower (p < 0.05) liver catalase activity compared to group 5. Additionally, groups 2 and 3 showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in liver catalase activity at week 12 compared to week 6

Figure 2: Liver Catalase Activities in Rats Administered with Oral Doses of Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac. Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine+ Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n=5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p<0.05). Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1, b Significant difference with groups 1, 2, 3, 6 and 8 be Significant difference with groups 6 and 8, c Significant difference with groups 1, 2, 4, 5 and 7, cd Significant difference with groups 1, 4, and 5, ce Significant difference with groups 1, 4, 5 and 7; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1, b Significant difference with group 1, ab No significant difference with groups 1, 2, 3, 4, 7 and 8 ac Significant difference with groups 6 and 7, abd Significant difference with group 5.*Significant difference between Week 6 and Week 12.

Figure 3 shows that at week 6, significant increases (p < 0.05) in serum paraoxonase concentration were recorded in groups 3, 4, 5, and 6 compared to the control and group 2. Group 5 also had higher (p < 0.05) serum paraoxonase 0.05) in serum paraoxonase levels compared to groups 3, 4, and 6, while group 7 had a significant decrease (p < 0.05) compared to groups 3, 4, 5, and 6. Group 8 also exhibited a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in serum paraoxonase concentration compared to groups 4, 5, and 6. At week 12, significant increases (p <0.05) in serum paraoxonase concentration were noted in groups 4 and 8 compared to group 2. In contrast, group 5 showed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) compared to group 3. Groups 6 and 7 had significantly lower (p < 0.05) serum paraoxonase levels compared to group 4, while group 8 had higher (p < 0.05) serum paraoxonase levels compared to groups 5 and 6. Additionally, groups 4, 5, and 6 exhibited a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in serum paraoxonase levels at week 12 compared to week 6.

Figure 3: Paraoxonase Concentrations in Serum of Rats Administered with Oral Doses of Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac. Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine+ Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n=5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p<0.05). Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1 ae No significant difference with groups 1, 3 and 7, bce Significant difference with groups 1, 2, 5, 7 and no significant difference with group 8, bd Significant difference with groups 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1, ab Significant difference with groups 4 and 8, acd Significant difference with groups 6 and 7, abce Significant difference with group 5, abcf Significant difference with groups 3 and 8, abg Significant difference with group 4, acg significant difference with groups 2, 5 and 6. * Significant difference between Week 6 and Week 12.

Effect of Artemether-lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac on Oxidative Products.

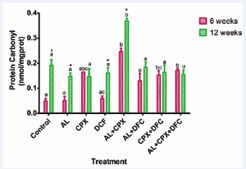

Figure 4 illustrates the levels of protein carbonyl in rats treated with artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac. After 6 weeks of treatment, a significant increase (p < 0.05) in serum protein carbonyl levels was observed in group 5 compared to the control (group 1) and groups 2, 4, and 6. Group 7 also exhibited a significant rise (p < 0.05) in serum protein carbonyl levels compared to the control and group 2. Similarly, group 8 showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in serum protein carbonyl levels compared to the control and groups 2 and 4. At week 12, group 5 displayed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in serum protein carbonyl levels compared to the control (group 1). Furthermore, significant increases (p < 0.05) in serum protein carbonyl levels were noted in groups 2, 4, and 5 at week 12 compared to week 6.

Figure 4: Serum Protein Carbonyl Concentrations in Rats Administered with Oral Doses of Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac. Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine+ Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n=5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p<0.05). Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1 b Significant difference with groups 1, 2, 4 and 6 ac Significant difference with group 8, abc No significant difference with group 1, 2, 4, 5, 5, 7 and 8; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1, b Significant difference with groups 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8. * Significant difference between Week 6 and Week 12.

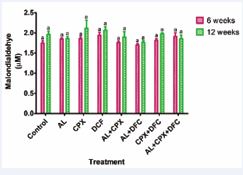

Figure 5 presents the liver malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations. No significant differences (p > 0.05), in liver MDA levels were found among the treatment groups 2,3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 compared to the control (group 1) at both week 6 and week 12. Similarly, there were no significant differences (p > 0.05), in serum MDA levels across the treatment groups at week 12 compared to week 6.

Figure 5: Serum Malondialdehyde Concentrations Activities in Rats Administered with Oral Doses of Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac. Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine+ Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n=5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p<0.05). Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1.

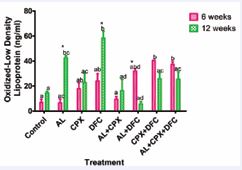

Figure 6 shows the serum concentrations of oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxidized-LDL) in rats treated with artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac. Significant increases (p < 0.05) in serum oxidized-LDL levels were observed in groups 7 and 8 compared to the control and groups 2 and 5 at week 6. Group 6 also had a significant increase (p < 0.05) in serum oxidized-LDL compared to group 2. At week 12, group 4 exhibited a significant rise (p < 0.05) in serum oxidized-LDL levels compared to the control, and groups 3, 5, 6, 7, and 8. Additionally, group 2 showed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in serum oxidized-LDL levels compared to the control, while groups 5 and 6 had significantly lower (p < 0.05) levels compared to group 2 at week 12. Significant increases (p < 0.05) in serum oxidized-LDL concentrations were also observed in groups 2 and 4 at week 12 compared to week 6, while a significant decrease (p < 0.05) was noted in serum oxidized-LDL levels of group 6 at week 12 compared to week 6.

Figure 6: Concentration of Oxidized-Low Density Lipoprotein in Serum of Rats Administered with Oral Doses of Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac. Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine+ Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n=5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p<0.05). Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1l b Significant difference with groups 1, 2 and 5 ab No significant difference with groups 1, 2, 5, 6 and 8, ac Significant difference with group 6, abd Significant difference with group 2; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1, b Significant difference with groups 1, 4, 5 and 6, ad Significant difference with groups 2, 3, 4, 7 and 8 , bc Significant difference with groups 1, 5 and 6. * Significant difference between Week 6 and Week 12.

Effect of Artemether-lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac on Oxidants

Figure 7 presents the heart nitric oxide levels in the treated rats. At week 6, groups 3 and 4 showed a significant elevetion (p < 0.05) in heart nitric oxide concentrations compared to the control (group 1). Additionally, group 3 had a significantly higher (p < 0.05) nitric oxide level compared to group 2. Conversely, group 6 exhibited a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in heart nitric oxide levels compared to groups 3 and 4, while group 8 had a significant increase (p < 0.05) compared to group 6 at the same time point.

Figure 7: Concentrations of Nitric Oxide in the Heart of Rats Treated with Oral Doses of Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac. Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). Values are presented as mean ± SEM; n=5. Mean values labelled with different letters show significant difference (p<0.05). Week 6: a No significant difference with group 1, b Significant difference with groups 1 and 6, ad Significant difference with groups 3 and 4, abc Significant difference with group 6, acd Significant difference with group 3, abcd No significant difference with groups 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8; Week 12: a No significant difference with group 1, b Significant difference with group 1, c Signicant difference with groups 1, 3 and 4, bd Significant difference with group 5.* Significant difference between Week 6 and Week 12.

At week 12, groups 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 demonstrated significant increases (p < 0.05) in heart nitric oxide levels relative to the control group. Groups 3 and 4 also had significantly elevated (p < 0.05) nitric oxide levels compared to groups 2, 5, 7, and 8. Furthermore, a significant decrease (p < 0.05) was noted in group 6 compared to group 3. In addition, groups 3, 4, 5, and 7 showed significant increases (p < 0.05) in heart nitric oxide levels at week 12 compared to week 6.

Histological Assessment of the Liver.

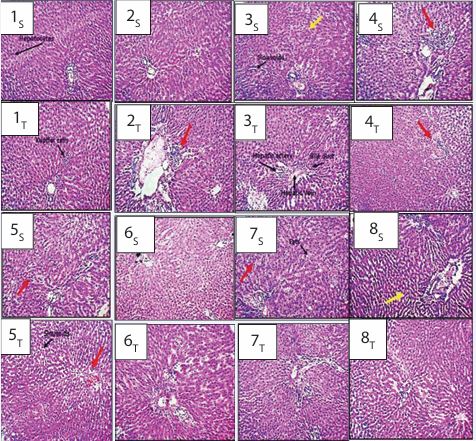

Plate 1 Photomicrographs of Liver Section of Control Rats Treated with Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac (H&E x 100). Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4- Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6- Artemether Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin+ Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). S= 6 weeks and T= 12weeks. 1S, 1T, 2S, 3T, 6 S, 6 T, 7T and 8T showed well nucleated hepatocytes, clear sinusoid without congestion, no signs of congestion coupled with a clearly outlined portal triad with no signs of dilation or infiltration of hepatic sinusoids by Kupffer cells. CX showed mildly observable micromophological alterations; mildly congested and infiltrated hepatic parenchymal and sinusoids, increased lymphocyte infiltration around the portal triad as well as observable periportal inflammatory cells infiltrates within the sinusoids and the entire hepatic paenchyma, portal triad dilatation, hemorrhagic appearance accompanied by mild focal sclerosis of the hepatic parenchyma, and hepatocytes appear pyknotic and mildly surrounded by fat (yellow arrow). 2T, 4S, 4T, 5S, 5T, 7S and 8T showed conspicuously observable micromophological alterations; severely congested and infiltrated hepatic parenchymal and sinusoids, increased lymphocyte infiltration around the portal triad as well as observable periportal inflammatory cells infiltrates within the sinusoids and the entire hepatic parenchyma, portal triad dilatation, hemorrhagic appearance accompanied by mild focal sclerosis of the hepatic parenchyma, and hepatocytes appear pyknotic and mildly surrounded by fat (red arrow).

Plate 1 presents photomicrographs of liver sections from control rats and those treated with artemether lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac. All groups (1-8) exhibited visible hepatocytes, sinusoids, and portal triads (hepatic vein, hepatic artery, and bile duct). For the control (group 1), no changes were observed in liver tissue profiles at both week 6 and week 12. The photomicrographs showed well nucleated hepatocytes, clear sinusoid without congestion, and clearly outlined portal triad with no signs of dilation or infiltration of hepatic sinusoids by Kupffer cells. Group 2 also showed no significant alterations at week 6. However, at week 12, severe morphological changes were evident, including congestion in the hepatic parenchyma and sinusoids, increased lymphocyte infiltration around the portal triad, and periportal inflammatory cell infiltration within the sinusoids and the hepatic parenchyma, as indicated by red arrows. The profile also shows portal triad dilatation, hemorrhagic appearance accompanied by mild focal sclerosis of the hepatic parenchyma. Hepatocytes in this group appear pyknotic and mildly surrounded by fat (red arrows). The photomicrograph of the liver section of group C showed mild observable micromorphological alterations as indicated with yellow arrows at 6 weeks while there was no observable alteration at week 12. Plate 1 also showed conspicuously observable micromophological alterations in the profiles of groups 4 and 5 at both week 6 and week 12 as indicated with red arrows. In addition, the profiles of the photomicrograph section of group 6 were intact at week 6, however, the red arrow indicated conspicuously observable alterations at week 12. Severe micromophological alterations were also observed in the liver section profiles of group 7 at week 6 (red arrow) while there was no observed micromophological alterations occurred at week 12. The yellow arrow in the photomicrograph of liver section of group 8 at week 6 also indicated mild observable micromophological alterations while there were no observable micromophological alterations at week 12.

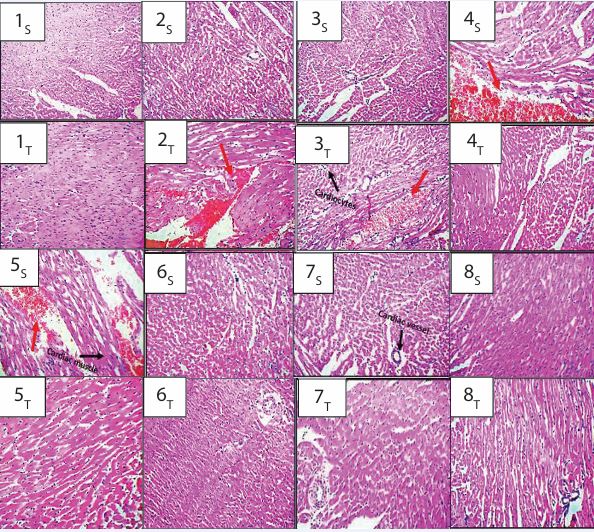

Histological Assessment of the Heart

Plate 2 illustrates the heart histomorphology for control rats and those treated with artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac.The epicardium myocardium and endocardium, and the intercalated discs and blood vessels are well demonstrated across groups A-H. In the control (group 1) and groups 6, 7, and 8, the myocardium maintained an intact profile with well preserved fenestrations/striations at both week 6 and week 12. Similarly, the photomicrographs of the heart histomorphology of groups 2 and 3 showed an intact profile at week 6, however, at week 12, cardiocytes were severely degenerated and distorted and fenestrations/ striations were conspicuously distorted. Other changes in this profile include marked degenerative changes/ clotted blood and mild fibrosis and loosely packed involuntary striated appearance is observable across the myocardium of these groups relative to the intact profiles. Furthermore, congested blood vessels coupled with clustered inflammatory cells are seen to infiltrate both the myocardium and endocardium as depicted with red arrows. In addition, the photomicrographs of groups 4 and 5 also showed degenerated and distorted cardiocytes as well as distorted fenstrtions/striations and other degenerative changes at week 6 as indicated with red arrows, however, the profiles of these groups were intact at week 12.

Plate 2 Photomicrographs of the Heart of Rats Treated with Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac (H&E x 100). Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6- Artemether Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin+ Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). S= 6 weeks and T= 12weeks. 1S, 1T, 2S, 3S, 4T, 5T, 6S, 6T, 7S, 7T, 8S and 8T showed an intact profile indicating intact fenestrations/striations across the myocardium. 2T, 3T, 4S and 5S showed severely distored and degenerated cardiocytes, distorted fenestrations/striations, marked degenerative changes/clotted blood and mild fibrosis, not very tightly packed involuntary striated appearance across the myocardium and infiltration of the myocardium and endocardium with congested blood vessels coupled with clustered inflammatory cells (red arrow).

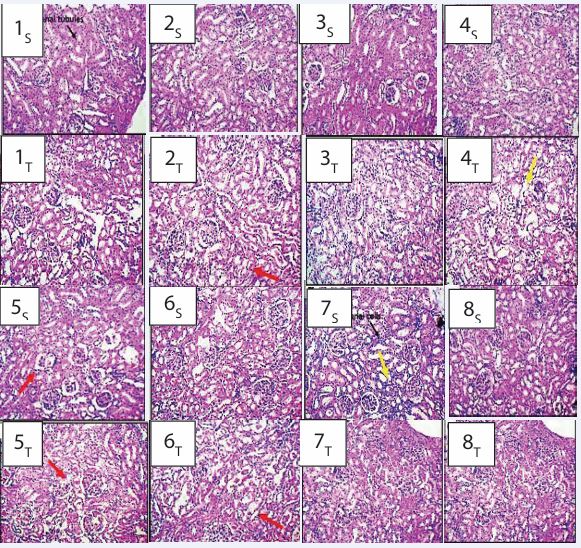

Histological Assessment of the Kidney

The representative photomicrographs of the kidney (renal tissue) micromorphological section demonstrated by Hematoxylin and Eosin staining across profiles of groups 1-8 is presented in Plate 3. The images clearly display various kidney structures, including the renal cortex, renal tubules, glomeruli, mesangial cells, proximal and distal renal convoluted tubules, renal corpuscle, and Bowman’s capsule. In the control (group 1), and groups 3 and 8, no significant observable changes were detected. These groups exhibited a normal and well-defined renal cortex, tubules, glomeruli, mesangial cells, and renal corpuscle, including Bowman’s capsule.

Plate 3: Photomicrographs of Kidney Section (renal tissue) of Rats Treated with Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac (H&E x 100). Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6- Artemether Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin+ Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). S= 6 weeks and T= 12weeks. 1S, 1T, 2S, 3S , 3T, 4S, 6S, 7T, 8S and 8T showed normal and well outlined renal cortex, renal tubules, glomeruli and renal & mesangial cells, and proximal and distal renal convoluted tubules, the renal corpuscle and Bowman’s capsule. 4T and 8S showed midly altered profile characterized by haemorrhage, infiltration by red inflammatory cells, glomerular nephritis (characterised by a collapsed capsular margin) and narrowed/congested renal tubules coupled with renal parenchymal fibrosis) (yellow arrow). 2T, 5S, 5T and 6T showed severely altered profile characterized by haemorrhage, infiltration by red inflammatory cells, glomerular nephritis (characterised by a collapsed capsular margin) and narrowed/congested renal tubules coupled with renal parenchymal fibrosis (red arrow).

Similarly, the profiles of groups 2, 4 and 6 showed a normal and well outlined profile in which there was no observable alterations at week 6, however, at week 12 alteration was observed characterized by haemorrhage, infiltration by red inflammatory cells, glomerular nephritis (characterised by a collapsed capsular margin) and narrowed/congested renal tubules coupled with renal parenchymal fibrosis as indicated with red arrows in group 2 and 6, while a mild histomorphocellular alteration was observed in group 4 and depicted with yellow arrow. As depicted by the red arrows, the photomicrograph of the kidney profile of group 5 also showed alterations characterized by haemorrhage, infiltration by red inflammatory cells, glomerular nephritis (characterized by a collapsed capsular margin) and narrowed/ congested renal tubules coupled with renal parenchymal fibrosis at both week 6 and week 12. In addition, a mild histomorphocellular alteration was observed in group 8 as indicated with yellow arrow at week 6 but an intact profile was seen at week 12 (Plate 3).

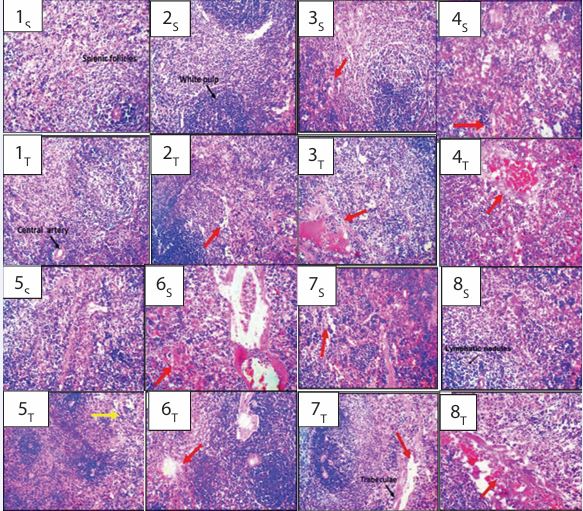

Histological Assessment of the Spleen

Plate 4: Photomicrographs of Spleen of Rats Treated with Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac (H&E x 100). Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6- Artemether Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin+ Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). S= 6 weeks and T= 12weeks. 1S, 1T, 2S, 5S and 8S showed well-organized white and red pulp with an easily discernible peri-arteriolar lymphocyte sheet, germinal centre, mantle zone and marginal zone. 5T a mildly altered micromophology was seen characterized with slight disorganized white/red pulp with either hyperplastic changes leading to a loss in the definition of the boundaries between the white and red pulp regions (yellow arrow). 2T, 3S, 3T, 4S, 4T, 6S, 6T, 7S, 7T and 8T a severely altered micromorphology characterized with fibrosis, poorly outlined connective tissue, degenerating cells of red and white pulps loss of connective tissue, and infiltrated splenic stroma and parenchyma (red arrow).

Plate 4 displays the photomicrographs of spleen micromorphology from control rats and those administered artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac. In the control group (1), the spleen tissues were well-organized, showing distinct white and red pulp structures, including clearly defined peri-arteriolar lymphocyte sheets, germinal centers, mantle zones, and marginal zones at both week 6 and week 12. Similarly, the photomicrograph of the spleen tissue of groups 2, 5 and 8 showed intact spleen tissues with well-organized white and red pulp at week 6, however at week 12, a severely altered micromorphology characterized with fibrosis, poorly outlined connective tissue, degenerating cells of red and white pulps loss of connective tissue, and infiltratedsplenic stroma and parenchyma were observed as indicated with red arrows in groups 2 and 8. Group 5 exhibited mild alterations, characterized by slightly disorganized white and red pulp and hyperplastic changes that led to a loss of distinct boundaries between these regions. Groups 3, 4, 6, and 7 also showed severe micromorphological changes at both week 6 and week 12, including fibrosis, poorly defined connective tissue, degeneration of red and white pulp cells, loss of connective tissue, and infiltration of splenic stroma and parenchyma, marked by red arrows. Additionally, the white and red pulp regions were extensively disorganized, with the follicular structure barely distinguishable from the surrounding red pulp and other areas (Plate 4).

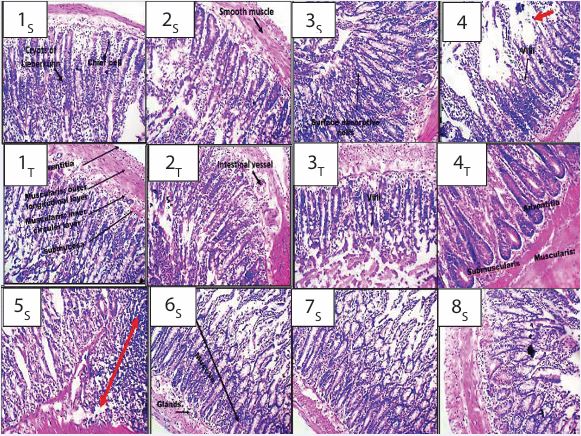

Histology Assessment of the Small Intestine

Plate 5 Photomicrographs of Small Intestine of Rats Treated with Artemether-Lumefantrine, Ciprofloxacin and Diclofenac (H&E x 100). Key: 1- Control, 2- Artemether-Lumefantrine (AL) 3- Ciprofloxacin (CPX), 4-Diclofenac (DFC), 5- Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin (AL+CPX), 6- Artemether Lumefantrine + Diclofenac (AL+DFC), 7- Ciprofloxacin + Diclofenac (CPX+DFC), 8 - Artemether-Lumefantrine + Ciprofloxacin+ Diclofenac (AL+CPX+DFC). S= 6 weeks and T= 12weeks. 1S, 1T, 2S, 2T, 3S , 3T, 4T , 6S, 7S and 8S showed normal presentation with no marked observable signs of alteration, with intact lamina propria and connective tissue. 4S , 5S, 5T , 6T , 7T and 8T showed severe Hypertrophy of the Muscularis layer, signs of aberrant foci crypts of Lieberkühn, presence of perforations as well as vacuolations across intestinal villi and Muscularis layer with some ulcerations, eroded lamina propria, signs of haemorrhage and some fibrosis (red arrow)

Plate 5 displays the photomicrographs of the small intestine from control rats and those treated with artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac. The intestinal layers-mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa-are clearly visible across all experimental groups (x100 magnification), with the distinctive finger-like projections (villi) lined by epithelium and lamina propria.In groups 1, 2, and 3, the small intestine appeared normal at both week 6 and week 12, with no significant alterations observed. The lamina propria and connective tissue remained intact throughout the study period. In contrast, group 4 showed severe changes at week 6, including hypertrophy of the muscularis layer, aberrant crypt foci of Lieberkühn, perforations, vacuolations in intestinal villi, muscularis layer ulcerations, eroded lamina propria, hemorrhage, and some fibrosis. By week 12, however, the intestinal morphology in group 4 returned to a normal appearance with no significant alterations.Groups 6, 7, and 8 also exhibited normal intestinal morphology at week 6, but by week 12, severe alterations similar to those seen in group 4 were observed. These included hypertrophy of the muscularis layer, aberrant crypt foci of Lieberkühn, perforations, vacuolations in villi, muscularis layer ulcerations, eroded lamina propria, hemorrhage, and fibrosis. Group 5 displayed severe morphological changes at both week 6 and week 12, including hypertrophy of the muscularis layer, aberrant crypt foci of Lieberkühn, perforations, vacuolations in intestinal villi, muscularis layer ulcerations, eroded lamina propria, hemorrhage, and fibrosis (Plate 5).

DISCUSSION

Oxidative Stress Indices

Oxidative stress is a state of imbalance between the production and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells and tissues and antioxidant defense mechanisms in the body [44,45]. Excessive oxidative stress results in oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA in cells and tissues and underlies numerous pathological conditions [46,47]. In biological systems, various antioxidant defense systems, including enzymatic and nonezymatic routes, act to regulate excessive levels of ROS [48]. Thiol groups are the first antioxidants that are consumed when the cells are exposed to oxidative stress and they can serve as a sensitive indicator of oxidative stress [49]. In addition, the induction of the major antioxidant enzymes (catalase and superoxide dismutase) reflects a specific response to pollutant oxidative stress [50].The recorded increases in activities of catalase in rats given combination of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac (Groups 5-8), and superoxide dismutase in rats administered with combination of ciprofloxacin and diclofenac (Group 7), reflected a possible response to counteract oxidative progression that might have resulted from the production of reactive oxygen species by the co-administered drugs. However, the decrease in reduced glutathione level and subsequent decrease in catalase activity in rats administered with ciprofloxacin and diclofenac (Group 7), at week 6 week and week 12 respectively suggested harmful effects of the drugs in the liver through excess undetoxified ROS (H2 O2 ), that could result in various pathological conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. This suggestion agreed with the observation from previous studies of Idowu et al. [32], who reported a significant decreases in the activities of catalase and superoxide dismutase in rats treated with artemether-lumefantrine, as well as the studies of Igbayilola et al. [34], and Elshopakey et al. [35], who reported that ciprofloxacin and diclofenac decreased the concentrations of reduced glutathione, superoxide dismutase and catalase respectively.Paraoxonase (PON) is a high-density lipoprotein (HDL) associated antioxidant enzyme that protects low-density lipoprotein (LDL) from oxidation by hydrolyzing the lipid peroxides in the oxidized lipoprotein [51] and has also been shown to play a significant role in the metabolism of pharmaceutical drugs [52]. It has been implied that PON ability to protect against oxidation is usually accompanied by an inactivation of the enzyme [53]. Hence, the subsequent decrease in paraoxonase activity at week 12 after the intial elevation at week 6 suggested time-dependent increased oxidative stress induced by the co-administration of artemether-lumefantrine and ciprofloxacin or diclofenac (groups 5 and 6). This is corroborated by the findings of Afolabi and Oyewo [54], who reported the inhibition of paraoxonase activity towards phenyl acetate by the fluoroquinolones, ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.In addition, the inability of biological system to eliminate free radical could results in oxidation of biomolocules such as lipids, proteins and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) [55]. Hence, protein carbonyl content in blood and tissues is a reliable indicator of protein oxidation [56]. The observed increase in the serum protein carbonyl concentration due to concomitant administration of artemether lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac is corroborated the pattern observed with the antioxidant enzymes in this study, and suggested an oxidative progression especially with long duration of administration. Oxidized-low density lipoprotein (oxidized-LDL) is formed as a result of oxidation, and it has many pathobiological significance [57]. Oxidation of low density lipoprotein (LDL), and the subsequent uptake by macrophages in the vascular wall, are important steps in the development of atherosclerosis [58]. A small fraction of the oxidized-LDL particles evades macrophage uptake by macrophages and either returns to the blood stream or leak from atherosclerotic plaques. Thus, measuring circulating levels of oxidized-LDL may contribute to the estimation of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk [23]. The elevation in the levels of oxidized-LDL observed in groups treated with combination of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac is simiilar to the trend of protein carbonyl, and might be a consequence of oxidative reactions of the co-administered drugs and suggested cardiovascular risks.Nitric oxide plays a crucial role in enhancing relaxation of smooth muscles and blood flow. However, over production of oxidized-low density lipoprotein has been linked with imbalanced activation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) that is responsible for the constituitive release of nitric oxide, thereby facilitating the activation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) which in turn enhances inflammatory processes within the vascular wall and contributes to arterosclerosis progression [59-61]. The concurrent increases in oxidized LDL and the production of nitric oxide in the heart of rats of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac, either singly or in combination in this study might be due inhibition of eNOS and subsequent activation of iNOS, and could result in the progression of arterosclerosis. The reaction of nitric oxide with superoxide to generate the highly reactive peroxynitrite has also been implicated in endothelial dysfunction [62]. This is in agreement with previous studies which reported that diclofenac treatment increased the concentration of nitric oxide [63]. The overall trend observed in this current study suggested that the individual and combined administration of artemether-lummefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac led to an oxidative stress state where the antioxidant defence system has not been overwhelmed. Notably, the oxidative progression was more prominent with co administration of the drugs and extented duration of administration. This asssertion is backed up by many studies in which it has been observed that drugs such as anti-inflammatory and analgesic could induce oxidative stress that is accompanied by increased cellular oxidants, oxidation of biomolocules such as lipids, proteins and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and induction of antioxidant enzymes [23,50,64].

Histological Analysis

The photomicrograph of the liver sections of the treatment groups in this present study clearly indicated a negative consequence of the drugs on the liver. The observed distortion of the cellular integrity of hepatic parenchymal and sinusoids following the single and combined administration of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac may be attributed to the liver’s exposure to high concentrations of exogenous substances and their metabolites. This is suggestive of a hepatotoxic effect of the drugs that could result in pathological conditions such as acute hepatitis and fibrosis. Hepatic damage can be caused by the drug metabolites generated in the liver through biotransformation, which can form toxic or reactive substances such as electrophilic chemicals or free radicals [65], thereby, resulting in either necrosis or apoptosis or both. Hence, the indicated toxic impacts of artemether-lumefantrine and ciprofloxacin might be due to the induction of oxidative stress in the liver by these drugs through the production of oxidative radicals, resulting in protein depletion in the hepatocytes. In addition, the hepatotoxicity of diclofenac might be due to the activities of its reactive metabolites including 4’-hydroxydiclofenac (4’ -OH-DCF), 5’-hydroxydiclofenac (5’ -OH-DCF) and the highly reactive benzoquinone imine derivatives. The pattern observed in this study is consistent with previously published reports of Owumi and Dim [33,66], who revealed that single administration artemether-lumefantrine and diclofenac caused degeneration of hepatocyte and mild fibrosis in liver tissues respectively. Similarly, Rajab and Turki [67] reported that ciprofloxacin caused changes such as dilated and congested blood vessels and acute swelling in liver tissues of rats S.typhi infected mice treated ciprofloxacin. The histological examination of the kidney sections of rats in groups 2, 5, 6 and 7 at week 6 and week 12, also revealed histomorphocellular alterations characterized by heamorrhage, infiltration by red blood cells, narrowed and congested renal tubule coupled with renal fibrosis. This might also be due to the frequent subjection of the kidneys to high concentrations of potentially toxic substances, since the kidneys serve as a primary route for the excretion of many drugs and their metabolic products. The depicted derrangement have been implicated in proximal tubular injury, acute tubular necrosis and interstitial nephritis [68,69]. The toxicities of the drugs in this study were severe with longer duration of administration in both single and co-administered treatment groups and may be linked to oxidative stress, resulting in lipid peroxidation and damage to cellular macromolecules. This opinion is supported by previous studies where separate administration of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac were associated with changes such as congestive blood vessels of the renal parenchyma with mononuclear cells filtration and dilation of the renal tubule [70-72].The depicted changes including distorted and degenerated cardiocytes, distorted fenestrations and striations and packed involuntary striated appearance in the myocardium in rats administered groups 2 and 3 at week 12 and groups 4 and 5 at week 6 suggested that the separate administration of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac, and co-administration of artemether-lumefantrine and ciprofloxacin have potential cardiotoxic effects. One critical observation of myocardial morphologic change in response to toxic compounds is heart hypertrophy which can lead to dilated cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and sudden death [73]. The mechanisms of cardiotoxicity induced by artemether lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac in this study might be due interaction of drugs and the generation of free radicals which may cause death of the cardiac muscles. This assertion is backed by previous studies of Ahmet et al. [74], where the mechanism of heart damage induced by ciprofloxacin was demonstrated to implicate oxidative stress. In addition, many studies have revealed that the antioxidant enzyme levels are relatively lower in the myocyte making this organ susceptible to reactive oxygen species [74] The histological examination of the spleen sections in this current study also showed that treatment with seperate and combined doses of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac at week 6 and week 12 altered the micromophorlogy of the spleen. This was characterized by degenerating white and red pulps, poorly outlined connective tissues, loss of connective tissue, fibrosis and infiltrated splenic stroma and parenchyma. This observed alteration in spleen micromorphology might be due to several factors including the formation of reactive metabolites and oxidative stress, altered immune function and hypersensitivity reactions. The findings in this study are inconsistent with previous studies that reported potent therapeutic effects of ciprofloxacin in the spleen along with the stimulation of the immune system with the active white pulp showing an increase in the number of lymphocytic cells and indicating an immune response [75,76]. This might be due to the variation in dose and duration of administration.The photomicrograph of the small intestine of the rats given diclofenac only and combinations of artemether lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin and diclofenac (groups 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) at week 6 and week 12 in this present study clearly indicated a negative effect of the drugs on the small intestine. This was characterized by hypertrophy of muscularis layer with some ulcerations, eroded lamina propia and signs of haemorrhage and fibrosis. The observed toxicity of the single administration of diclofenac as well as its combination with artemether-lumefantrine and ciprofloxacin on the small intestine in this study might be due the formation of reactive metabolites and inhibition of prostanglandins, which are important for maintaining the integrity of the stomach and intestinal lining by diclofenac, as well as the induction of oxidative stress by artemether-lumefantrine and ciprofloxacin, and disruption of the intestinal barrier. The observed alteration in the small intestine profiles of the treatment groups could result in serious gastrointestinal complications such as development of ulcers, bleeding, perforations and inflammation in the small intestine. The trend in this study agreed with other studies that reported that ulcerated lesions were seen in the mesenterial border of intestinal mucosa of rats who received diclofenac [77].

CONCLUSION

From the foregoing, the combined administration of artemether-lumefantrine, ciprofloxacin, and diclofenac resulted in an imbalance in the oxidative status with concomitant predisposition to cardiovascular disorders and derangements in the liver, kidney, heart, spleen and small intestine. The risks associated with the administration of these drugs were especially higher with concurrent administration of the drugs compared with their separate use, particularly with extended durations of administration. Thus, our findings emphasized the need for caution when considering the combination, prolonged use, and or, abuse of these drugs.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval (BMS/AIEC/0147/21) was obtained from the Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology.

Authors Contributions

Study Design: Emmanuel Oyewo and Juliana Ajayi. Data collection: Juliana Ajayi and Peace Ige. Software and Statistical analysis: Juliana Ajayi and John Fatoki. Data Interpretation: Juliana Ajayi, Emmanuel Oyewo and Adeniran Adekunle. Manuscript Preparation: Juliana Ajayi, Emmanuel Oyewo, Adeniran Adekunle, John Fatoki and Peace Ige. Literature Search: Ajayi Juliana and Emmanuel Oyewo. Supervision: Emmanuel Oyewo, John Fatoki and Adeniran Adekunle. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Ayanwale MB, Kolade Y, Adeoye OA, Bamisile RT. Self-medication practices among workers in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Int J Tropical Dis Health. 2017; 26: 1-11.

- Bassi PU, Osakwe AI, Builders M, Ette E, Kola AI, Bing B, et al. Prevalence and determinants of self medication practice among Nigerians. Afr J Health Sci. 2021; 34: 634-648.

- Ruiz ME. Risks of self-medication practices. Curr Drug Saf. 2010; 5: 315-323.

- Lawan UM, Abubakar IS, Jibo AM. Drug abuse among youths and self-medication pattern among students of Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria. J Biol Scientific Opinion. 2013; 1: 215-222.

- Mehta R, Sharma S. Self-medication among healthcare professionals in a tertiary care hospital, Delhi. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2015; 2: 710-714.

- Babatunde OO, Fadare JO, Ojo OJ, Durowade KA. Self-medication among health workers in a tertiary institution in South-West Nigeria. J Health Res. 2016; 18: 13-19.

- World Health Organiation. Malaria prevention works, let’s close the gap. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switerland. 2017.

- Mooney JP, Galloway LJ, Riley EM. Malaria, Aneamia and Invasive bacteria disease: A neutrophil problem? J Leukoc Biol. 2019; 105: 645-655.

- Umoh IU, Ekanem TB, Eluwa MA, Bassey UE. Fetal hepatorenal toxicity of artemether/lumefantrine (coartem®) in second trimester of pregnancy in albino rats. Eur J Pharmaceutical Med Res. 2017; 4: 240-246

- Woodro CJ, Haynes RK, Krishna S. Artemisinins: Mechanism of action. Postgraduate Med J. 2005; 81: 71-78.

- Little RJ, Pestano AA, Parra Z. Modeling of peroxide activation in artemisinin derivatives by serial docking. J Mol Modeling. 2019; 15: 847-858.

- Moein S, Farzami B, Khaghani S, Moein MR, Larijani B. Antioxidant properties and prevention of cell cytotoxicity of Phlomispersica Boiss. DARU J Phamaceutical Sci. 2007; 15: 83-88.

- Umeke OE, Obiako RO, Chukwuocha UM, Nwoke BE. Malaria and enteric fever co-infection among febrile out-patients in South- Eastern Nigeria. The Internet J Infectious Dis. 2008; 6: 1-8.

- Galadima MB, Muhammad A, Sani U, Ahmad M. Prescription pattern of antimalarial and antibiotic co-administration among healthcare providers in Kano, Nigeria. J Pharmaceutical Res Int. 2020; 32: 1-10.

- Uwah AF, Ndem JI, Akpan EJ. Combining Artesunate-Amodiaquine and ciprofloxin improves serum lipid profile of mice exposed to plasmodium bergheiberghie. Int J Biomed Res. 2014; 5: 487-489.

- Sinem I, Ozgur DC, Ozhem A, Umut IU. Ciprofloxacin induced neurotoxicity: evaluation of possible underlying mechanisms. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2015; 5: 374-381.

- Albesa I, Becerra MC, Battan PC. Oxidative stress involved in the antibacterial action of different antibiotics. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004; 317: 605-609.

- Goswami M, Mangoli SH, Jawali N. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in the action of ciprofloxacin against Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003; 50: 949-954.

- Kohanski MA, Dwyer DJ, Hayete B. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell J. 2007; 130: 797-810.

- Wang X, Zhao X. Contribution of oxidative damage to antimicrobial lethality. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007; 53: 1395-1402.

- Ojiako OA, Nwanjo HU. Analgesic and antipyretic drugs use in an urban Nigerian community. West African J Pharm. 2007; 17: 40-45.

- Iqbal Z, Khan A, Naz A, Khan AJ, Khan SG. Pharmacokinetic Interaction of ciprofloxacin and diclofenac: A single dose, two period crossover study in healthy adults volunteers. Clin Drug Investig. 2009; 29: 1-6.

- Oyewo EB, Ajayi JO, Adekunle AS, Oso JB. Oxidative stress indices and inflammatory responses in female Wistar rats administered acetaminophen, ampicillin/cloxacillin, and co-trimoxazole. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2021; 38.

- Hawkins C, Hanks GW. The gastroduodenal toxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020; 20: 140-151.

- He BS, Wang J, Liu J. Eco-pharmacovigilance of nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs: necessity and opportunities. Chemosphere. 2017; 181: 178-189.

- O’Connor N, Dargan PI, Jones AL. Hepatocellular damage from non- steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Quaterly J Med. 2003; 96: 787-

-

791.Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Derry S. Non-prescription (OTC) oral analgesics for acute pain—an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005; 4: CD010794.