Turning the spotlight on the perplexing case of Colpocephaly: Exhuming its pathophysiology and symptomatology

- 1. Merit Health Wesley Health Center, USA

- *. Both authors contributed equivocally and regarded co-first authors

Abstract

Colpocephaly is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by disproportionate dilatation of the occipital horns of the lateral ventricles due to impaired neuronal migration. Fewer than 30 adult cases have been reported in the literature. We describe a 60-year-old male who presented with panic attacks and headache, in whom neuroimaging revealed posterior cortical atrophy, hypoplasia of the septum pellucidum, parietal white matter disease, and features consistent with colpocephaly. While this condition typically presents in childhood with seizures, developmental delay, and cognitive impairment, adults are often asymptomatic and rarely present with nonspecific symptoms such as headache or dizziness. Diagnosis is radiologic, and management is limited to symptomatic treatment, as no definitive therapy exists. This case underscores the importance of recognizing colpocephaly in adults and differentiating it from normal pressure hydrocephalus, which carries very different clinical and therapeutic implications.

Keywords

• Colpocephaly

• Neurodevelopmental disorder

• Lateral ventricles

• Occipital horns

• Frontal horns

• Corpus callosum

• Ventriculomegaly

• Arachnoid cyst

• Normal pressure hydrocephalus

• Shunting

Citation

Kanuri SH, Beauti S, Messenger K (2025) Turning the spotlight on the perplexing case of Colpocephaly: Exhuming its pathophysiology and symptomatology. J Pharmacol Clin Toxicol 13(2):1194.

INTRODUCTION

Colpocephaly is the abnormal dilation of the posterior horns of the lateral ventricles [1]. It occurs due to congenitally abnormal neurodevelopment, due to which the occipital horns enlarge predominantly [2]. In some instances, it is associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum [2]. It is caused by numerous factors, ranging from toxins, infections, chromosomal abnormalities, and usage of steroids during pregnancy, to anoxic encephalopathy [3]. In most instances, it presents in childhood with neurodevelopmental abnormalities [4,5]. Nevertheless, in older age groups, it can present with seizures, headache, and intellectual disabilities [3,6]. Diagnosis is made with imaging, and it should be mainly differentiated from NPH and arachnoid cysts [7]. Treatment is symptomatic, as there is no specific therapy available. As of 2025, there are fewer than 20–30 adult cases of colpocephaly reported in the literature [8]. Therefore, we present this adult case of colpocephaly presenting with panic attacks and headache, which on imaging revealed the classic signs of this clinical disorder.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old male, retired from the military and currently a full-time student, presented to the emergency department with a severe panic attack. He described experiencing several panic attacks that were sometimes manageable with coping techniques, but this particular day was severe, so he went to the ER. He had never had head imaging prior to this. He had no history of concussion and no known seizures. He also had a history of occasional vertigo and blurred vision corrected with contact lenses. As part of his evaluation, a non-contrast head CT was performed, which demonstrated posterior cortical atrophy and enlargement of the occipital horns of the lateral ventricles, suggestive of colpocephaly. These findings were considered incidental, and the patient was referred to Neurology by his primary care provider for further evaluation.

At the time of outpatient neurology evaluation, he described frequent migraines occurring more than three times weekly. These typically began in the occipital region and progressed to holocephalic pain, occasionally associated with nausea and, rarely, projectile vomiting. He also reported intermittent vertigo and episodes of blurred vision, corrected with contact lenses. He denied seizures, head trauma, or concussion. Past medical history was notable for migraines and anxiety. Neurological examination was non-focal, with intact cranial nerves, normal strength and reflexes, and no dysmorphic features..

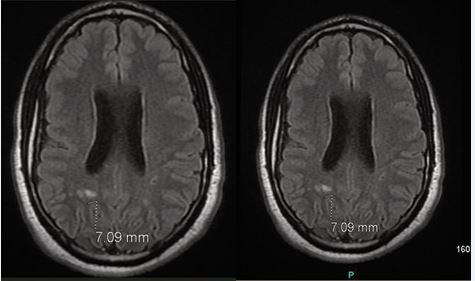

Figure A MRI brain without contrast:

Brain MRI without contrast (Figure A), demonstrated a pattern of colpocephaly with cavum septum pellucidum and mild ventriculomegaly, as well as nonspecific foci of demyelination in the posterior periventricular white matter tracts, measuring up to 7 mm and more prominent on the right hemisphere as compared to the left hemisphere. No evidence of acute infarction, hemorrhage, or mass effect was observed. An EEG was performed to further evaluate for subclinical seizures and showed no epileptiform activity.

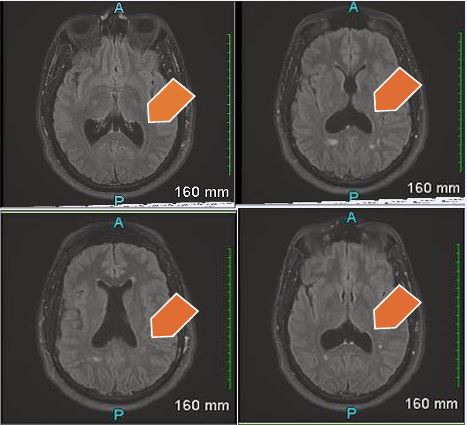

Figure B MRI Brain with contrast – Hypoplasia of the septum pallucidum. Corpus callosum is intact. Trace scattered white matter disease primarily in the parietal lobe. There is enlargement of the posterior horns of the lateral ventricles, suggesting colpocephaly.

A subsequent contrast-enhanced MRI (Figure B), confirmed hypoplasia of the septum pellucidum with mild colpocephaly and an intact corpus callosum. Additionally, there was scattered white matter disease in the parietal lobes without abnormal enhancement. The ventricular findings were unchanged from the prior study.

In summary, this patient was found to have colpocephaly with associated hypoplasia of the septum pellucidum and nonspecific periventricular white matter changes, identified incidentally during evaluation for an unrelated panic attack and further characterized with serial MRI studies. Given the diagnosis, the patient was recommended symptomatic treatment for his headaches and panic attacks. Regular follow-up is advised to monitor his symptom resolution.

Ventricles of the brain are somewhat prominent for a patient of this age. Cavum of the septum pallucidum. Pattern of colpocephaly. Mild ventriculomegaly is noted. Non-specific foci of demyelination are seen in the posterior periventricular white matter tracts in both the hemispheres more prominent on the right side than left. These range from 3-7 mm. No Acute infarct. No hemorrhage.

DISCUSSION

We present a case of colpocephaly in a 32-year-old male with no pertinent medical history, who presented with severe panic attacks and headache. On further testing, he was found to have a predominant dilation of the posterior horns of the lateral ventricles on MRI brain. These findings were associated with hypoplasia of the septum pellucidum, scattered white matter disease in the parietal lobe, and demyelination of the white matter tracts in both hemispheres. This abnormality usually presents in childhood, and its late presentation in adults is quite unusual. With this clinical case, we would like to highlight the abnormal radiological findings and its unusual symptomatology in the older age population. Although there are no specific treatment approaches available for this abnormality, symptomatic treatment and multimodality approaches are recommended.

This disorder was originally identified by Clemens Benda, an American psychiatrist, in 1940 as vesiculocephaly, where he described a clinical case of a child with epilepsy and microcephaly harboring enlarged primary brain vesicles [9]. Later, Yakovlev and Wadsworth (1946) coined the term colpocephaly to denote enlarged occipital horns of the lateral ventricles and described its pathological basis [10].

Pathophysiologically, anomalous neuronal migration or halting in white matter development can be factors that lead to the inception of colpocephaly [11,12]. The occipital horns of the lateral ventricles are abnormally dilated (3:1) as compared to the frontal horns [12,13]. As white matter development is halted in the occipital lobe, the posterior horns of the ventricles gradually enlarge and fill the space created in the posterior lobe [14]. Furthermore, any defects in fetal neurodevelopment can perpetuate the persistence of fetal ventricular shape, leading to colpocephaly [3]. The physiological decrease in the size of the occipital horns of the lateral ventricles by myelination of ventricular wall fibers, corpus callosum, forceps fibers, the parieto-occipital fissure, and calcarine fissure is disrupted by developmental arrest, thus leading to the formation of colpocephaly [15]. During the 5th month of fetal development, migration of glial cells along with growth of the corpus callosum and white matter is stifled, opening the doors for the development of posterior ventriculomegaly characteristic of colpocephaly [16].

Some of the risk factors that can provoke colpocephaly include perinatal injuries, intrauterine infections, perinatal anoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, intrauterine growth retardation, maternal usage of corticosteroids, maternal exposure to toxins, chromosomal abnormalities 8 and 9, congenital toxoplasmosis, meningococcal meningitis, and X-linked chromosomal inheritance [2,3,12].

Colpocephaly may not be an isolated finding. In most instances, colpocephaly is bilateral, but unilateral cases have been reported in hemimegalencephaly and porencephaly [17]. It may be part of a broad spectrum of neurological disorders related to anomalous neuroblast development or arrest in neuronal cell migration [12,15]. Concomitant neurological disorders associated with colpocephaly include agenesis of the corpus callosum, Arnold–Chiari malformation, lissencephaly, microcephaly, myelocele, macrogyria, microgyria, schizencephaly, cerebellar atrophy, optic nerve atrophy, periventricular leukomalacia, and larger cisterna magna [3,12]. Furthermore, it can be associated with various syndromes, including lissencephaly type 1, linear nevus sebaceous syndrome, Marden–Walker syndrome, Tourette syndrome, Aicardi syndrome, Norman–Roberts syndrome, Zellweger syndrome, Nijmegen breakage syndrome, hemimegalencephaly, and Chudley–McCullough syndrome [17].

Most commonly, colpocephaly is diagnosed in children due to its associated neurological abnormalities [12]. Although its clinical presentation in adults is rare, it may present with symptoms ranging from headache, dizziness, seizures, motor or sensory disturbances, cognitive slowing, intellectual lapses, visual hallucinations, and poor academic performance [2,3,12,15]. Psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have also been associated with colpocephaly. Fetuses with Trisomy 18 frequently have colpocephaly along with congenital cardiac defects, including atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, and polyvalvular disease [18,19].

In this case, our patient presented with panic attacks and recurrent headache, and upon further workup, it was revealed that he had colpocephaly. He did not have the associated congenital abnormalities discussed above. There was no pertinent past medical history, childhood symptoms, or significant perinatal birth history that could be linked to colpocephaly in our patient. On further probing, he did not experience any cognitive, behavioral, or learning disabilities.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of colpocephaly is CT (computed tomography) scan and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). The hallmark signs include disproportionate ballooning of the occipital horns of the lateral ventricles as compared to the frontal horns. Some researchers have postulated measuring the posterior anterior (P/A) ratio, which is the maximum width of the posterior horns divided by the width of the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles [4]. A P/A ratio greater than 3 indicates abnormal enlargement of the occipital horns, thus supporting the diagnosis of colpocephaly [7,20]. Specifically, colpocephaly should be distinguished from NPH, and assessing the P/A ratio is helpful in this scenario [7]. Clinical history identifying the classical triad of dementia, gait disturbance, and urinary incontinence, normal CSF pressure, ventricular dilation, and Evan’s index > 3 are telltale signs of NPH [7]. This distinction is important because NPH is progressive and obstructive, thus warranting surgical shunts to relieve the obstruction [21]. Furthermore, colpocephaly should be distinguished from arachnoid cysts, which are intra-hemispheric fissures frequently associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum, thus necessitating cystoperitoneal shunts [22].

Colpocephaly associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum is identified by a “race car sign,” where the frontal horns, body, and lateral horns of the lateral ventricles assume a Formula One racing car shape on axial imaging [23]. As colpocephaly is diagnosed, efforts should be made to administer symptomatic treatment, as there is no specific therapy available for this rare clinical disorder. Patients presenting with seizures should be prescribed anti-epileptics [2]. Other patients with neurological, cognitive, or learning symptoms should be referred for multimodal approaches, including neurology, occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech therapy, and physiotherapy [3,24].

CONCLUSIONS

Colpocephaly is an uncommon neurodevelopmental disorder caused by arrest in glial cell migration as well as restricted growth of the corpus callosum, leading to the development of ventriculomegaly. CT scan/MRI revealing disproportionate ballooning of the occipital horns as compared to the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles confirms the diagnosis. Although often asymptomatic, it can be associated with seizures, headache, learning disabilities, and cognitive impairment. It should be differentiated from NPH, as the latter requires numerous diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. There is no specific treatment for colpocephaly other than symptomatic management.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, S.H.K & SB; Methodology, S.H.K & S.A; Software, N.G.; Validation, N.A; Formal Analysis, N.A.; Investigation, S.H.K & VP.; Resources, N.A.; Data Curation, N.A.; Writing– Original Draft Preparation, S.H.K & S, B.; Writing– Review & Editing, S.H.K.& S.B.; Visualization, S.H.K.; Supervision, K.M..; Project Administration, K.M.

REFERENCES

- Cheong JH, Kim CH, Yang MS, Kim JM. Atypical meningioma in the posterior fossa associated with colpocephaly and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2012; 113: 167-171.

- Mirzaei S, Motaghed Z, Zarei H. Colpocephaly and corpus callosum dysgenesis in an adult: A rare case report. Int J Surgery Case Rep. 2024; 124: 110484.

- Sangwan A, Meena R. Colpocephaly in an adult: A rare case report.Radiol Case Rep. 2024; 19: 2048-2051.

- Noorani PA, Bodensteiner JB, Barnes JB. Colpocephaly: frequency andassociated findings. J Child Neurol. 1988; 3: 100-104.

- Nasrat T, Seraji-Bozoergzad N. Incidentally discovered colpocephaly and corpus callosum agenesis in asymptomatic elderly patient. Ibnosina J Med Biomed Sci. 2015; 7: 56-58.

- Wunderlich G, Schlaug G, Jancke L, Benecke R, Seitz RJ. Adult-onset complex partial seizures as the presenting sign in colpocephaly: MRI and PET correlates. J Neuroimaging. 1996; 6: 192-195.

- Esenwa CC, Leaf DE. Colpocephaly in adults. BMJ Case Rep. 2013.

- Edzie EKM. Colpocephaly in a 62-year-old woman: a case report. ArchClin Med Case Rep. 2020; 4: 1009-1013.

- BENDA CE. Microcephaly. Am J Psychiatr. 1941; 97: 1135-1146.

- Yakovlev PI, Wadsworth RC. Schizencephalies; a study of the congenital clefts in the cerebral mantle; clefts with fused lips. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1946; 5: 116-130.

- Ciurea RB. Corpus callosum dysgenesis and colpocephaly. Rom JNeurol. 2013; 12: 160-163.

- Parker C, Eilbert W, Meehan T, Colbert C. Colpocephaly Diagnosed in a Neurologically Normal Adult in the Emergency Department. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019; 3: 421-424.

- Landman J, Weitz R, Dulitzki F, Shuper A, Sirota L, Aloni D, et al. Radiological colpocephaly: a congenital malformation or the result of intrauterine and perinatal brain damage. Brain Dev. 1989; 11: 313- 316.

- Jumaan AAA, Tahseen WM. Colpocephaly and corpus callosum agenesis in an asymptomatic adult. Bahrain Med Bull. 2019; 41: 275- 277.

- Bennaoui F. Colpocephaly, a Very Rare Neonatal Brain Malformation: a Case Report and Literature Review. Int J Clin Case Reports and Rev. 2010; 23: 01-05.

- Puvabanditsin S, Garrow E, Ostrerov Y, Trucanu D, Illic M, CholenkerilJV. Colpocephaly: a case report. Am J Perinatol. 2006; 23: 295-297.

- Seyfettin ULUDA? YA, Begüm AYDO?AN, Burcu AYDIN. A Very Rare Case of Colpocephaly Associated With Trisomy 18. Gynecol Obstet Reprod Med. 2012; 18: 83-85

- Van Praagh S. Cardiac malformations in trisomy-18: a study of 41 postmortem cases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989; 13: 1586-1597.

- Musewe NN, Alexander DJ, Teshima I, Smallhorn JF, Freedom RM. Echocardiographic evaluation of the spectrum of cardiac anomalies associated with trisomy 13 and trisomy 18. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990; 15: 673-677.

- Bartolomé EL. Asymptomatic colpocephaly and partial agenesis ofcorpus callosum. Neurologia. 2016; 31: 68-70.

- Esmonde T, Cooke S. Shunting for normal pressure hydrocephalus(NPH). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002: Cd003157.

- Ulu MO. Treatment of symptomatic interhemispheric arachnoid cystsby cystoperitoneal shunting. J Clin Neurosci. 2010; 17: 700-705.

- Agarwal DK, Patel SM, Krishnan M. Classical Imaging in CallosalAgenesis. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2018; 13: 118-119.

- Mahmoud A, Mekheal E, Varghese V, Michael P. Can a Cerebral Congenital Anomaly Present in Adulthood?” Cureus. 2022; 14: e31985.